Meaningless Relics

Note: This was originally published on my blog on July 7, 2023

Let’s take a break from the world of sports card NFTs for a moment and dive into a convention of modern physical cards that serves as a great example of how the trading card companies take an idea, run it into the ground, and then make it so meaningless that collectors forget what made them interesting to begin with (and saving these companies a lot of money in the process.

I’m talking about relic cards–aka memorabilia “mem” cards or jersey/patch cards.

The definition of relic has some amusing context with this story:

relic

noun

rel·ic ˈre-lik

1 a : an object esteemed and venerated because of association with a saint or martyr

b : SOUVENIR, MEMENTO

2 relics plural : REMAINS, CORPSE

3 : a survivor or remnant left after decay, disintegration, or disappearance

4 : a trace of some past or outmoded practice, custom, or beliefBy the time we get to the end, you’ll get the joke if you don’t already.

Beckett has a concise history of these cards that’s worth a read, but the origin story goes back to 1996 when they made their debut from the mainstream card companies. That year there were 151 relic cards, which were a huge product chase for the companies making them. They were special and they were game-used. By 1999 the number had grown to 1,048 cards and when 2001 was done the total was 15,452. The peak as of that article was in 2005 when there were 78,954 relic cards produced.

This is a pretty standard pattern in trading card history. Something new comes along and unexpectedly becomes huge. Then companies adjust to the demand but the margins don’t improve due to acquisition/production costs increasing. That leads to companies cutting corners to try to fill the need at a lower cost, which kills the appeal of the original item or the novelty just wears off. And then everyone is looking for the next hype cycle.

What is interesting about the relic cards though were some of the particular issues they caused companies looking for material to create them. For relic cards of historic players there have been controversies about destroying game-used uniforms to make cards with people arguing these items shouldn’t be cut up. There also have been many examples of questionable provenance for “game-used” relics or outright frauds.

It’s fun rabbit hole to go down if you’re relatively new to card collecting because many of the issues surrounding these cards are part of the core struggles in the hobby between collectors and the card companies.

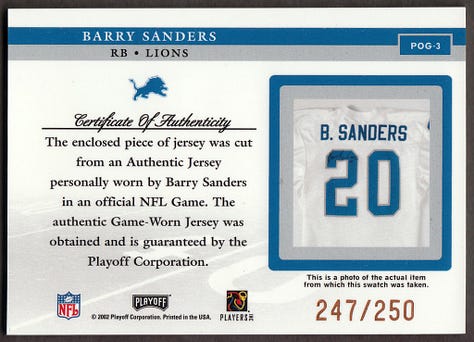

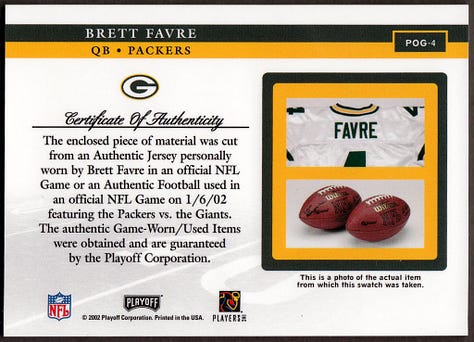

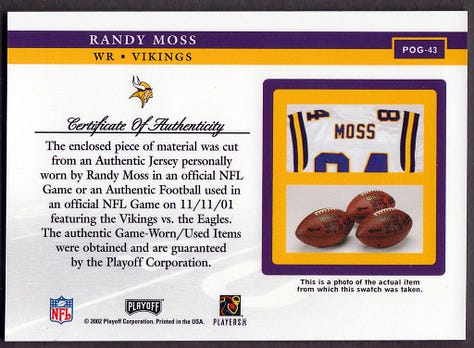

My favorite relic cards were from the run up to the peak production: 2002 Playoff NFL Piece of the Game. If my memory is correct, this was the first product that had a relic card in every pack. This wasn’t a cheap product at the time, but obviously this was at a point that these relic cards were easier to pull. What I liked about them was the transparency for their source material: you got a photo of the items used for that player’s cards and in some cases you even had the game it was from identified. Playoff did this for some of their other products of this era as well. I put together some examples to illustrate what these cards looked like at the bottom of this post.

That type of detail may not be something companies what to legally expose themselves to now, but as a collector it was a really fun experience. Not only did you know this stuff was game-used (as much as you trust these companies), but for the specific games you could look up how that player did in the game the relics were from.

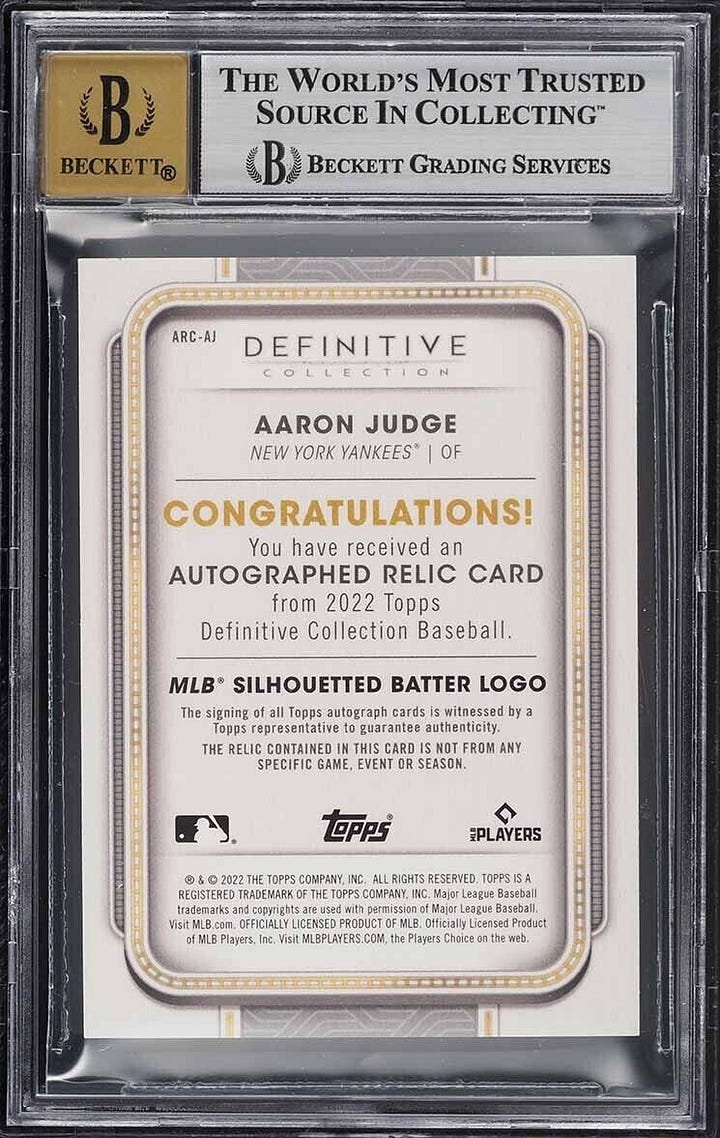

I have to laugh when I see what collectors get now for the most coveted cards these days: the “logoman” cards that have relics from the league logo on the uniform. When these first came out they were extremely hard to pull and due to being one per uniform there weren’t many made. Now players have multiple logomen cards in some individual products. How does that work? Well, these are now “not associated.” That could mean they came from uniforms worn by other players or uniforms not worn by anyone (in a game or otherwise). And it could mean they even come from uniforms not player-issued (i.e. off the rack). This is true for these most special patch relics as well as the rest of the relics in these products.

Compare the provenance for the relics above to these from 2022 products that I pulled off eBay.

An interesting side effect of this cost-saving and production-friendly approach by Topps and Panini (among others) is it has created a niche for short print true game-used relics with solid provenances to be produced by some of the non-officially licensed card companies like Leaf. Is an unlicensed card with a game-used logoman that has a solid history better than a licensed rookie logoman that could be from a store bought jersey? It’s an interesting question modern collectors are going to have to wrestle with.

I think this is also an interesting point to raise with physical collectors who like to make fun of digital collectors spending money on “fake cards.” If your relic card has nothing to with the player on it, is that really much better?

I hope you enjoyed this slice of something different and I’d love to hear your thoughts about this topic. Be sure to check out some of those links for more examples from the history of these cards that brought some new excitement to the hobby even if everyone doesn’t love them now.